We’wha and Nancy were two lhamana among the Zuni people of the American Southwest in the mid- to late 1800s and early 1900s. “Lhamana” is an identity for a person whose dress and behavior do not correspond with that person’s apparent physiological sex. In terms of Gay culture, We’wha may be considered a transwoman and Nancy a transman, identities that may nevertheless be judged inaccurate because they do not take into account the cultural nuances of Zuni gender identities, situated in folk custom and cosmology in ways that may not be easily classified by non-Zuni people.

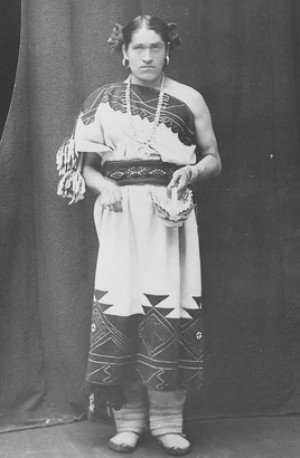

We’wha. Photo: John K. Hillers, cerca 1871-cerca 1907 (commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/ File:We-Wa,_a_Zuni_berdache,_full_length_portrait_-_NARA_-_523798.tif, January 2013)

We’wha became famous after accompanying an anthropologist (Matilda Cox Stevenson) to major cities in the USA, including Washington, DC, where she sang, danced, and gave demonstrations of pottery-making, weaving, and ritual from Zuni folklife. Scandal erupted when news of her male physiology reached the news media.

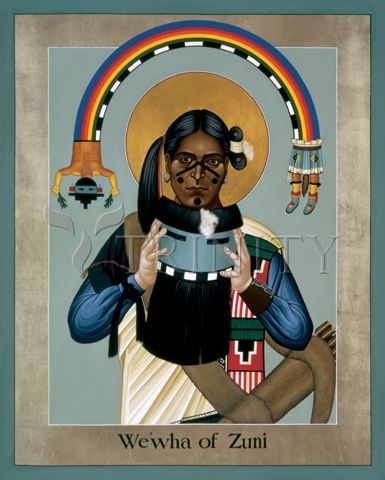

We’wha is a legendary figure among the Zuni, and an icon in the Two-Spirit (referring to a number of alternative gender and orientation identities found among Native peoples in North America) LGBTQ community. Little information about Nancy is available, however, reflecting a trend in ethnographic scholarship prior to the end of the twentieth century to focus on males more so than females.

Photo: John K. Hillers (commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:We-Wa,_a_Zuni_berdache,_weaving_-_NARA_-_523796.jpg, January 2013)

Lhamana and Gender

Gender identity as understood in Zuni (also known as A:shiwi) culture is the result of socializing and training deemed appropriate for women, socializing and training appropriate for men, and the preference of a child for one or the other. All children are born neutral, and maturity consists in being trained in an appropriate gender and social identity that is determined by the society and the individual. In general, female children will be attracted to those things defined as feminine such as cooking and pottery-making, and male children to masculine things such as hunting and farming.

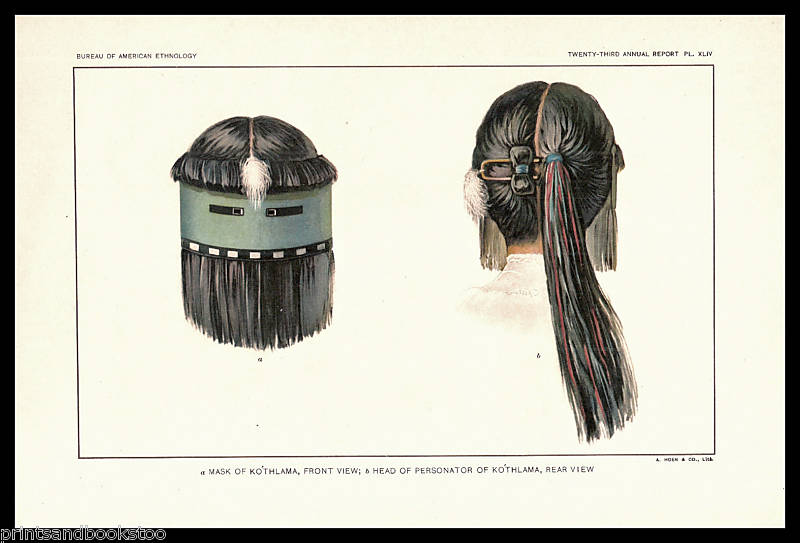

Should a child’s biological sex not match its inclinations, that child may be allowed to take on aspects of dress, behavior, and identity of the other gender. The term for such a person among the Zuni is lhamana. Among the Zuni, both male and female lhamana have been known to join men’s Kachina societies and take on the role of Kolhamana, the half-man/half-woman Kachina. The Kachinas are beloved deities that embody social, agricultural, natural, and cosmic themes.

There are similar traditions in other Pueblo Indian communities such as the Hopi, Keres, Tiwa, and Tewa (who have hova, kokwimu, lhunide, and kwidó, their respective equivalents of lhamana), neighboring tribes like the Navajo (with nádleehi identity), and by Native peoples throughout North America. With Christian missionaries, however, came pressure to abandon those identities.

Traditional identities, contemporary problems: Fred Martinez, a 16-year-old who identified as nádleehi, and was murdered in Cortez, Colorado in 2001. (today.colostate.edu/story.aspx?id=4828, January 2013)

Nancy

Nancy, born female but who behaved in the manner of men, is briefly mentioned by anthropologist Elsie Clews Parsons in Parsons’ field research conducted during the 1910s. Little is known about Nancy other than a preference for a more masculine identity, and the acceptance Nancy received from the community. Nancy was a Zuni lhamana (caveat: not all accounts of lhamana recognize the possibility that a female person could be lhamana) who was jokingly called katsotsi, a mannish woman, from otsotsi or “masculine.” Nancy was initiated into a sacred Kachina society of the community and wore the mask and dress of Kolhamana during certain ceremonies.

Kolhamana mask and hairstyle, 1901 (ebay.com/itm/1901-Print-44-Zuni-Indian-Religion-Dance-Kothlama-MASK-/370161924728, January 2013)

Lhamana may perform a combination of gender traits rather than adherence to one or the other. In terms of male lhamana, the individual will often be addressed in third person as a woman, but nevertheless recognized as male, as was the case of We’wha. On the other hand, Nancy appears to have been addressed as “she” and “her,” but nevertheless seen as katsotsi.

From Lhamana to “Zuni Princess”

We’wha was born in 1849 in Zuni Pueblo, New Mexico, about 150 miles west of Albuquerque. Not much is known about her childhood other than she was orphaned when smallpox took her parents. As was the custom, a young boy’s preference for things defined by the Zuni as feminine placed that child in the status of lhamana, and most likely this was the case for We’wha.

Having made a name for herself as a potter, weaver, and community leader, We’wha gained the attention of anthropologist Matilda Cox Stevenson, who had come to Zuni to conduct field research. We’wha accompanied Stevenson to Stevenson’s home near Dupont Circle in Washington, DC, where We’wha was acclaimed a “Zuni princess” (alternatively, “Zuni priestess,” “Zuni maiden,” and “Zuni girl”), became a celebrity among the Washington elite, and stayed a few days in the White House as the guest of President Grover Cleveland.

Photo: circa 1895 (amertribes.proboards.com/index.cgi?board=southwest&action=display&thread=641, January 2013)

Native American scholars take issue with the terms used by non-Native writers to describe We’wha. Responding to We’wha being described as a “princess,” Two-Spirit activist Crisosto Apache made the following statement for the Encyclopedia of Gay Folklife:

The term “princess” should never be used in describing Native American culture. Although it is apparent that We’wha was an important part of her culture, “princess” is not the correct term to define her reputation and relationship to her people. She might have been considered an ambassador, or plainly an esteemed representative.

The canonization of We’wha as Zuni LGBTQ saint: Brother Robert Lentz, OFM, has made images of certain cultural figures into saints by portraying them in a Greek Orthodox icon format. Brother Lentz did the same with We’wha, accessorizing (right or wrong) rainbow imagery to reflect both Native American and LGBTQ symbols (trinitystores.com/store/art-image/we-wha-zuni-1849-1896, January 2013)

We’wha was not the first Zuni to visit Washington, but she was perhaps the first woman, and she traveled without the company of other Zunis. As such, her poise, sophistication, and gender created a media frenzy unmatched by those Zuni who had come before her. Her height (two meters) and masculine facial features notwithstanding, she became the living embodiment of romantic fantasies of the Indian maiden in European American folklore before the press realized she was not born female.

Visibility

For the most part, gender variation and same-sex erotic-romantic love was either erased or condemned in early European and European American accounts of Native culture. We’wha was given national media attention due to European American ignorance of Zuni gender identities and political hierarchies. The revelation of her male biological sex was a scandal to those European Americans who thought We’wha was female, since We’wha had been granted access to the private rooms for women wherever she went. For We’wha and the Zuni people, however, there was no scandal at all. The very fact that the Zuni saw no problem with her feminine identity is what allowed her to be framed as a woman within the strictly bifurcated gender roles of European Americans in the late 1800s.

Had We’wha been presented to European Americans as a male Zuni woman from the start, however, she would never have been allowed to do the things she had done in Washington. She would not have been acclaimed a “Zuni princess” by the press, and would surely not have been a guest who stayed for days in the White House. Whether by accident or design by her sponsor, Matilda Stevenson, the unconditional classification of We’wha as a Zuni woman opened doors for her and gained her national exposure that would have been difficult for a Zuni man. It also gave LGBTQ history a landmark moment when a president of the United States in the nineteenth century befriended a gender-variant person.

What little attention was given to gender variation by ethnographers before Stonewall tended to be fixated on feminine men. Although it is easy to see how We’wha could be so sensationalized and visible because of her stay in Washington and the media sensation she inspired, there is much more information about womanish men than mannish women in anthropological accounts around the world, not just Native peoples of North America. Women and transmen in the LGBTQ community have sought out examples of similar identities in ethnographic accounts, and individuals such as Nancy are becoming less like incidental footnotes.

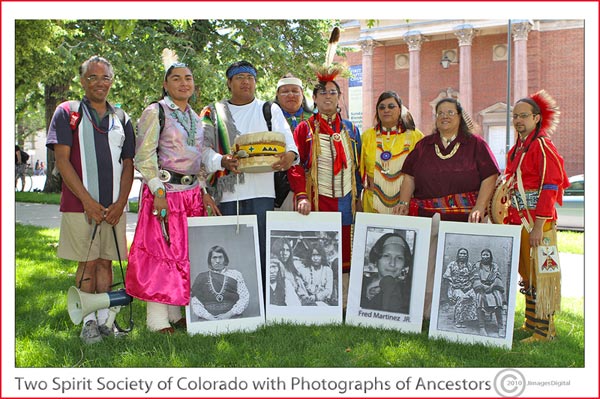

Two Spirit Society of Colorado at Denver’s Pridefest, displaying pictures of Two-Spirit ancestors, including We’wha and Fred Martinez, 2010. Photo: Jim Austin (apogeephoto.com/july2010/jaustin72010.shtml, January 2013)

We’wha died in 1896. There is no information as to the year in which Nancy was born or passed away. When We’wha died, she received a traditional Zuni burial befitting a person of her stature. Respect accorded to her included placing a pair of pants on her legs so that all aspects of her being, including the masculine, went with her to the afterlife.

– Mickey Weems

QEGF Authors and Articles

QEGF Introduction

Comments? Post them on our Encyclopedia facebook page.

Further reading:

Lang, Sabine. Men as Women, Women as Men: Changing Gender in Native American Cultures. Austin: University of Texas, 1998.

Roscoe, Will. The Zuni Man-Woman. Alburquerque: University of New Mexico, 1991.