Zap is an unannounced protest that generates publicity with little investment in time and money. The term takes its name from “zap,” a sudden shock of electricity. Zaps constitute an important genre of Gay activist folk performance since the Stonewall Awakening in Greenwich Village, Manhattan in June 1969.

Shouting Down Opposition, Serving them Coffee

Zaps originated with the Gay Activists Alliance (GAA), which was founded in New York City in December 1969. The goal of the GAA was to get pro-Gay voices heard. When such voices were not given the opportunity to speak, the GAA would plan a zap. Early zaps included the unexpected interruption of presentations by unmarked activists in the audience. If a professor, psychologist, or politician were to give a speech on how homosexuality was unhealthy, perverse, or unholy, activists in the audience would shout at the speaker until a medically, legally, and spiritually neutral stance could be established as a baseline for discussion, or until the activists were forcefully removed from the premises.

Zaps also featured humorous performance. In response to an anti-Gay article published in Harper’s magazine in September 1970, the GAA demanded the chance for a rebuttal, but were refused. In October, Harper’s business office was zapped by the GAA. According to Elizabeth Armstrong, activists set up a table in the reception area with coffee and doughnuts, distributed leaflets, and introduced themselves to the employees: “Good morning. I’m a homosexual. We’re here to protest the Epstein article. Would you like some coffee?”

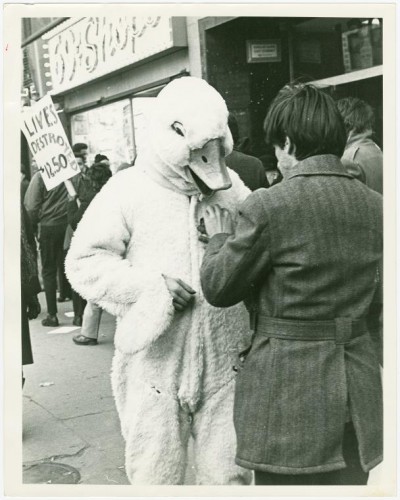

Activist Marty Robinson in his duck suit: “GAA 1971 Protest of Fidelifacts for bragging about ‘outing’ gays in the workplace. Photo by Richard C. Wandel” (picasaweb.google.com/115059132693404041853 /HistoricTSEventsSigns#5325291867648718482, January 2013)

In 1971, the president of Fidelifacts (a New York private investigative agency that specialized in ferreting out homosexual people) was asked how he knew if somebody was homosexual. “If it walks like a duck, talks like a duck, it’s a duck,” he answered. The Gay Activist Alliance staged a zap with Marty Robinson in a duck costume in front of the agency’s offices. The media captured the moment, leading to public ridicule of the agency.

Zaps, AIDS, and ACT UP

When the AIDS crisis hit in the mid-1980s, groups such as ACT UP used zaps to alert the public to the severity of the epidemic. Many of the zap techniques were from the early days of Gay liberation – activists chained themselves in front of establishments, and shouted down those who refused to address the problem or likened AIDS to divine punishment. As was true with most Gay protests, ACT UP encouraged protesters to be confrontational, even angry, but not violent.

Phone Zaps, Fax Zaps

Zaps included phone zaps and fax zaps. Phone zaps are designed to tie up the phone lines with callers making demands on the targeted person or group. Some fax zaps were basically the same as phone zaps (tying up the system without damaging it) but others were more destructive. It was possible, for example, to send a fax of a black sheet of paper in such a way as to continuously jam the recipient’s fax machine and use up the recipient’s ink.

Die-In, Kiss-In

As street performance, one favorite zap during the first years of the AIDS crisis was the die-in, a variation of the sit-in (takeover of buildings by protestors who would sit down and refuse to leave). On cue, activists would silently collapse and lie prone while other activists would outline the bodies with chalk.

March 2009: In front of the Notre Dame Cathedral in Paris, ACT UP-Paris protesters staged a die-in to protest the homophobia and anti-condom rhetoric of Pope Benedict XIV (formes-vives.org/histoire/?post/act-up, January 2013)

The kiss-in is a more blatantly Queer variant, with same-sex couples kissing en masse. Kiss-ins would be used by other LGBTQ activist groups to protest organizations, such as the Promise Keepers (a Christian-based men’s group) at Columbus, Ohio’s Nationwide Arena in 2001, and the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-Day Saints in 2009 after two men were arrested on the property of the Tabernacle in Salt Lake City for kissing each other in public.

2012: “April 2, several gay couples hugged and kissed in the street of Guangzhou City. They hope to have attention and respect from the public through this way. On the sign board they held, the slogan reads, ‘Support legalizing same-sex marriage; love together, love bravely, and respect same-sex love.'” (asiansmack.info/2012/04/gay-kiss-in-takes-place-in-street-of.html, January 2013)

Glitter Bomb

Glitter became the weapon of choice for some activists in the first two decades of the twenty-first century. Any media figure considered homophobic was a candidate for a glitter bomb (having glitter thrown onto them). Politicians who were glitter-bombed included homophobic Republican candidates for president during the run for 2012, such as Newt Gingrich and Rick Santorum.

Santorum getting glitter bombed in Lady Lake, Florida, January 2012. He had been glitter bombed some days prior in South Carolina (postonpolitics.com/2012/01/santorum-avoids-glitter-bomb-at-rowdy-town-hall -says-he-disagrees-that-americans-wont-vote-for-mormon, January 2013)

– Mickey Weems

QEGF Authors and Articles

QEGF Introduction

Comments? Post them on our Encyclopedia facebook page.

Further reading:

Armstrong, Elizabeth Ann. Forging Gay Identities: Organizing Sexuality in San Francisco, 1950 – 1994. Chicago: University of Chicago, 2002.

Campbell, J. Louis. Jack Nichols, Gay Pioneer: “Have You Heard My Message?” New York: Routledge, 2007.

Teal, Don. The Gay Militants: How Gay Liberation Began in America, 1969-1971. New York, St. Martin’s, 1971.